One of the largest sources of confusion in the question of blockchain security is the precise effect of the block time. If one blockchain has a block time of 10 minutes, and the other has an estimated block time of 17 seconds, then what exactly does that mean? What is the equivalent of six confirmations on the 10-minute blockchain on the 17-second blockchain? Is blockchain security simply a matter of time, is it a matter of blocks, or a combination of both? What security properties do more complex schemes have?

Note: this article will not go into depth on the centralization risks associated with fast block times; centralization risks are a major concern, and are the primary reason not to push block times all the way down to 1 second despite the benefits, and are discussed at much more length in this previous article; the purpose of this article is to explain why fast block times are desirable at all.

The answer in fact depends crucially on the security model that we are using; that is, what are the properties of the attackers that we are assuming exist? Are they rational, byzantine, economically bounded, computationally bounded, able to bribe ordinary users or not? In general, blockchain security analysis uses one of three different security models:

- Normal-case model: there are no attackers. Either everyone is altruistic, or everyone is rational but acts in an uncoordinated way.

- Byzantine fault tolerance model: a certain percentage of all miners are attackers, and the rest are honest altruistic people.

- Economic model: there is an attacker with a budget of $X which the attacker can spend to either purchase their own hardware or bribe other users, who are rational.

Reality is a mix between the three; however, we can glean many insights by examining the three models separately and seeing what happens in each one.

The Normal Case

Let us first start off by looking at the normal case. Here, there are no attackers, and all miners simply want to happily sing together and get along while they continue progressively extending the blockchain. Now, the question we want to answer is this: suppose that someone sent a transaction, and k seconds have elapsed. Then, this person sends a double-spend transaction trying to revert their original transaction (eg. if the original transaction sent $50000 to you, the double-spend spends the same $50000 but directs it into another account owned by the attacker). What is the probability that the original transaction, and not the double-spend, will end up in the final blockchain?

Note that, if all miners are genuinely nice and altruistic, they will not accept any double-spends that come after the original transaction, and so the probability should approach 100% after a few seconds, regardless of block time. One way to relax the model is to assume a small percentage of attackers; if the block time is extremely long, then the probability that a transaction will be finalized can never exceed 1-x, where x is the percentage of attackers, before a block gets created. We will cover this in the next section. Another approach is to relax the altruism assumption and instead discuss uncoordinated rationality; in this case, an attacker trying to double-spend can bribe miners to include their double-spend transaction by placing a higher fee on it (this is essentially Peter Todd’s replace-by-fee). Hence, once the attacker broadcasts their double-spend, it will be accepted in any newly created block, except for blocks in chains where the original transaction was already included.

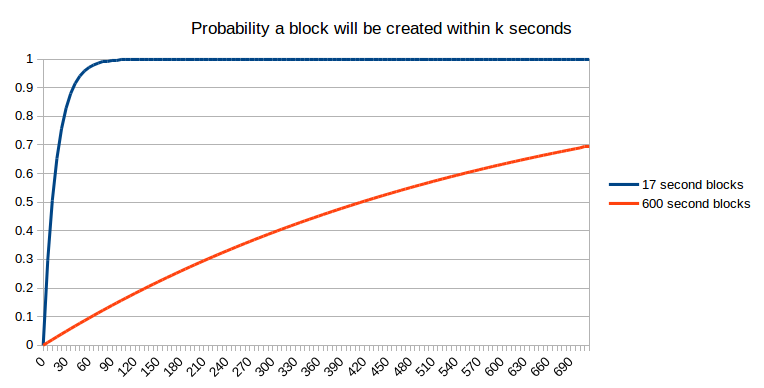

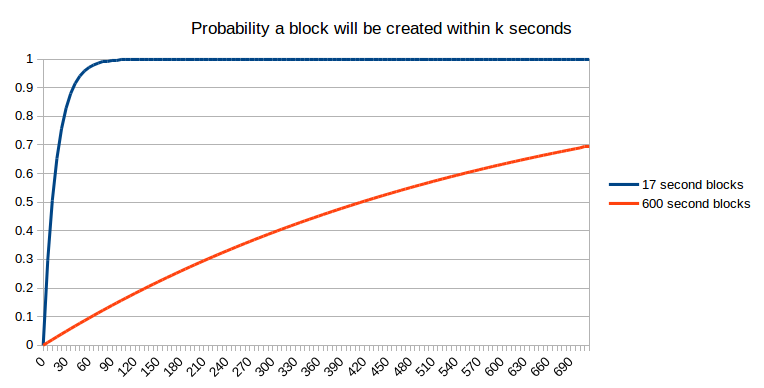

We can incorporate this assumption into our question by making it slightly more complex: what is the probability that the original transaction has been placed in a block that will end up as part of the final blockchain? The first step to getting to that state is getting included in a block in the first place. The probability that this will take place after k seconds is pretty well established:

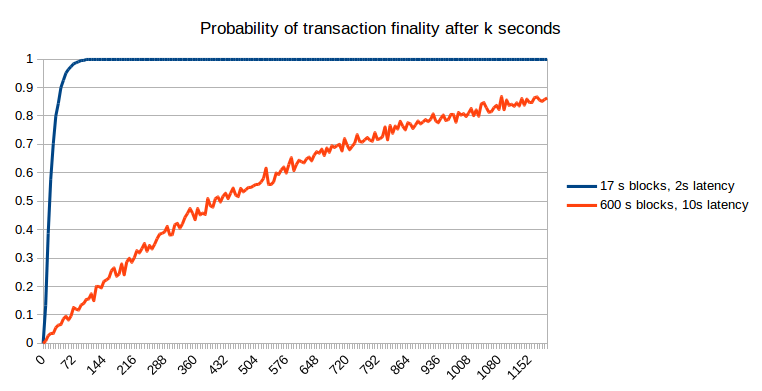

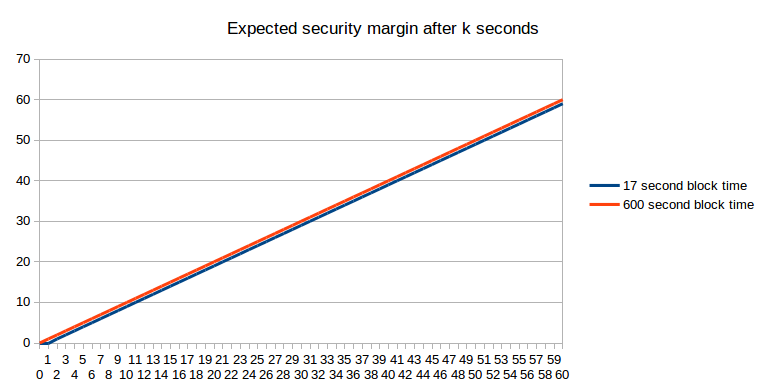

Unfortunately, getting into one block is not the end of the story. Perhaps, when that block is created, another block is created at the same time (or, more precisely, within network latency); at that point, we can assume as a first approximation that it is a 50:50 chance which of those two blocks the next block will be built on, and that block will ultimately “win” – or, perhaps, two blocks will be created once again at the same time, and the contest will repeat itself. Even after two blocks have been created, it’s possible that some miner has not yet seen both blocks, and that miner gets lucky and created three blocks one after the other. The possibilities are likely mathematically intractable, so we will just take the lazy shortcut and simulate them:

The results can be understood mathematically. At 17 seconds (ie. 100% of the block time), the faster blockchain gives a probability of ~0.56: slightly smaller than the matheatically predicted 1-1/e ~= 0.632 because of the possibility of two blocks being created at the same time and one being discarded; at 600 seconds, the slower blockchain gives a probability of 0.629, only slightly smaller than the predicted 0.632 because with 10-minute blocks the probability of two blocks being created at the same time is very small. Hence, we can see that faster blockchains do have a slight disadvantage because of the higher influence of network latency, but if we do a fair comparison (ie. waiting a particular number of seconds), the probability of non-reversion of the original transaction on the faster blockchain is much greater.

Attackers

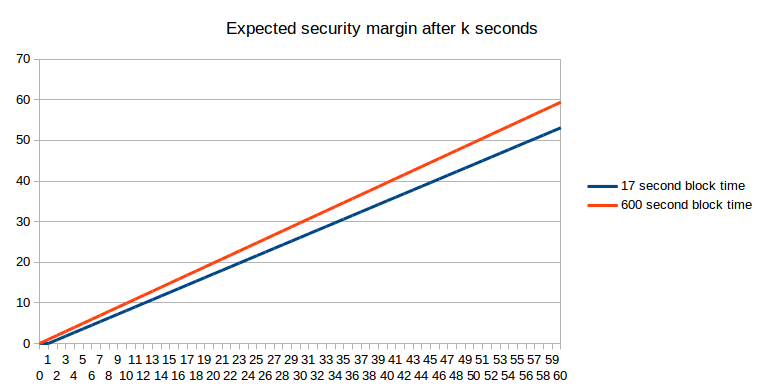

Now, let’s add some attackers into the picture. Suppose that portion X of the network is taken up by attackers, and the remaining 1-X is made up of either altruistic or selfish but uncoordinated (barring selfish mining considerations, up to X it actually does not matter which) miners. The simplest mathematical model to use to approximate this is the weighted random walk. We start off assuming that a transaction has been confirmed for k blocks, and that the attacker, who is also a miner, now tries to start a fork of the blockchain. From there, we represent the situation with a score of k, meaning that the attacker’s blockchain is k blocks behind the original chain, and at every step make the observation that there is a probability of X that the attacker will make the next block, changing the score to k-1 and a probability of 1-X that honest miners mining on the original chain will make the next block, changing the score to k+1. If we get to k = 0, that means that the original chain and the attacker’s chain have the same length, and so the attacker wins.

Mathematically, we know that the probability of the attacker winning such a game (assuming x as otherwise the attacker can overwhelm the network no matter what the blockchain parameters are) is:

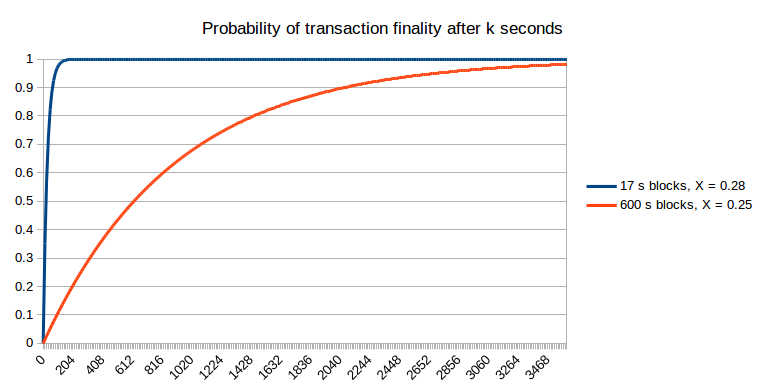

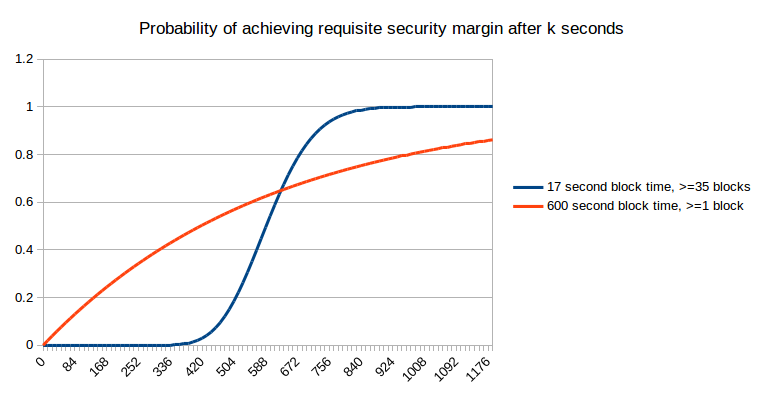

We can combine this with a probability estimate for k (using the Poisson distribution) and get the net probability of the attacker winning after a given number of seconds:

Note that for fast block times, we do have to make an adjustment because the stale rates are higher, and we do this in the above graph: we set X = 0.25 for the 600s blockchain and X = 0.28 for the 17s blockchain. Hence, the faster blockchain does allow the probability of non-reversion to reach 1 much faster. One other argument that may be raised is that the reduced cost of attacking a blockchain for a short amount of time over a long amount of time means that attacks against fast blockchains may happen more frequently; however, this only slightly mitigates fast blockchains’ advantage. For example, if attacks happen 10x more often, then this means that we need to be comfortable with, for example, a 99.99% probability of non-reversion, if before we were comfortable with a 99.9% probability of non-reversion. However, the probability of non-reversion approaches 1 exponentially, and so only a small number of extra confirmations (to be precise, around two to five) on the faster chain is required to bridge the gap; hence, the 17-second blockchain will likely require ten confirmations (~three minutes) to achieve a similar degree of security under this probabilistic model to six confirmations (~one hour) on the ten-minute blockchain.

Economically Bounded Attackers

We can also approach the subject of attackers from the other side: the attacker has $X to spend, and can spend it on bribes, near-infinite instantaneous hashpower, or anything else. How high is the requisite X to revert a transaction after k seconds? Essentially, this question is equivalent to “how much economic expenditure does it take to revert the number of blocks that will have been produced on top of a transaction after k seconds”. From an expected-value point of view, the answer is simple (assuming a block reward of 1 coin per second in both cases):

If we take into account stale rates, the picture actually turns slightly in favor of the longer block time:

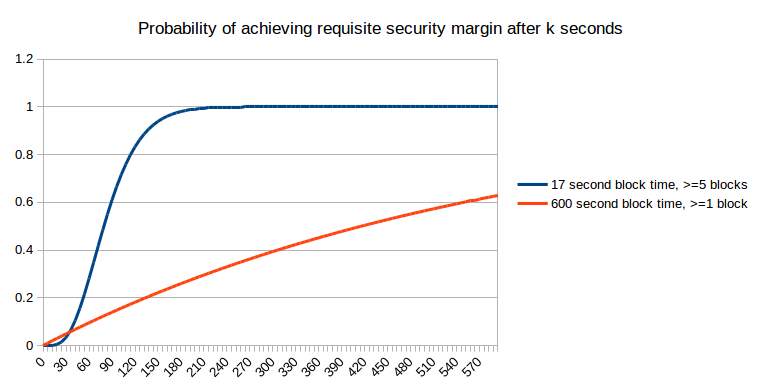

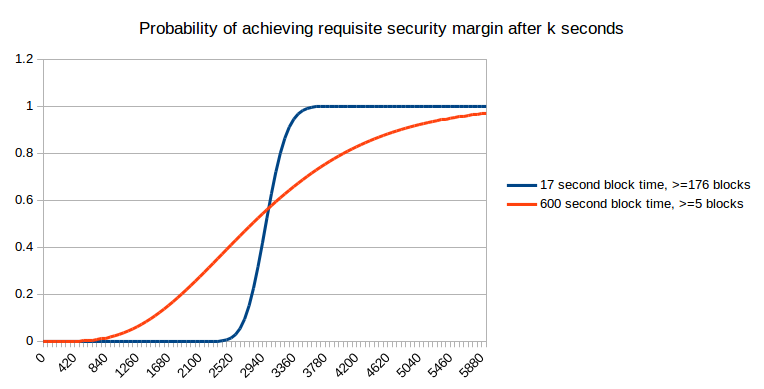

But “what is the expected economic security margin after k seconds” (using “expected” here in the formal probability-theoretic sense where it roughly means “average”) is actually not the question that most people are asking. Instead, the problem that concerns ordinary users is arguably one of them wanting to get “enough” security margin, and wanting to get there as quickly as possible. For example, if I am using the blockchain to purchase a $2 coffee, then a security margin of $0.03 (the current bitcoin transaction fee, which an attacker would need to outbid in a replace-by-fee model) is clearly not enough, but a security margin of $5 is clearly enough (ie. very few attacks would happen that spend $5 to steal $2 from you), and a security margin of $50000 is not much better. Now, let us take this strict binary enough/not-enough model and apply it to a case where the payment is so small that one block reward on the faster blockchain is greater than the cost. The probability that we will have “enough” security margin after a given number of seconds is exactly equivalent to a chart that we already saw earlier:

Now, let us suppose that the desired security margin is worth between four and five times the smaller block reward; here, on the smaller chain we need to compute the probability that after k seconds at least five blocks will have been produced, which we can do via the Poisson distribution:

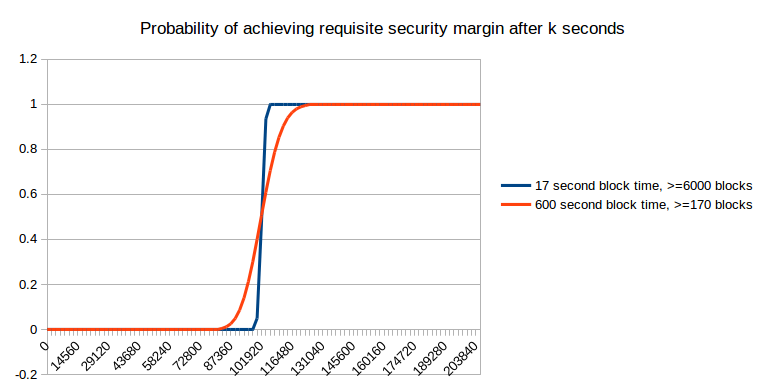

Now, let us suppose that the desired security margin is worth as much as the larger block reward:

Here, we can see that fast blocks no longer provide an unambiguous benefit; in the short term they actually hurt your chances of getting more security, though that is compensated by better performance in the long term. However, what they do provide is more predictability; rather than a long exponential curve of possible times at which you will get enough security, with fast blocks it is pretty much certain that you will get what you need within 7 to 14 minutes. Now, let us keep increasing the desired security margin further:

As you can see, as the desired security margin gets very high, it no longer really matters that much. However, at those levels, you have to wait a day for the desired security margin to be achieved in any case, and that is a length of time that most blockchain users in practice do not end up waiting; hence, we can conclude that either (i) the economic model of security is not the one that is dominant, at least at the margin, or (ii) most transactions are small to medium sized, and so actually do benefit from the greater predictability of small block times.

We should also mention the possibility of reverts due to unforeseen exigencies; for example, a blockchain fork. However, in these cases too, the “six confirmations” used by most sites is not enough, and waiting a day is required in order to be truly safe.

The conclusion of all this is simple: faster block times are good because they provide more granularity of information. In the BFT security models, this granularity ensures that the system can more quickly converge on the “correct” fork over an incorrect fork, and in an economic security model this means that the system can more quickly give notification to users of when an acceptable security margin has been reached.

Of course, faster block times do have their costs; stale rates are perhaps the largest, and it is of course necessary to balance the two – a balance which will require ongoing research, and perhaps even novel approaches to solving centralization problems arising from networking lag. Some developers may have the opinion that the user convenience provided by faster block times is not worth the risks to centralization, and the point at which this becomes a problem differs for different people, and can be pushed closer toward zero by introducing novel mechanisms. What I am hoping to disprove here is simply the claim, repeated by some, that fast block times provide no benefit whatsoever because if each block is fifty times faster then each block is fifty times less secure.

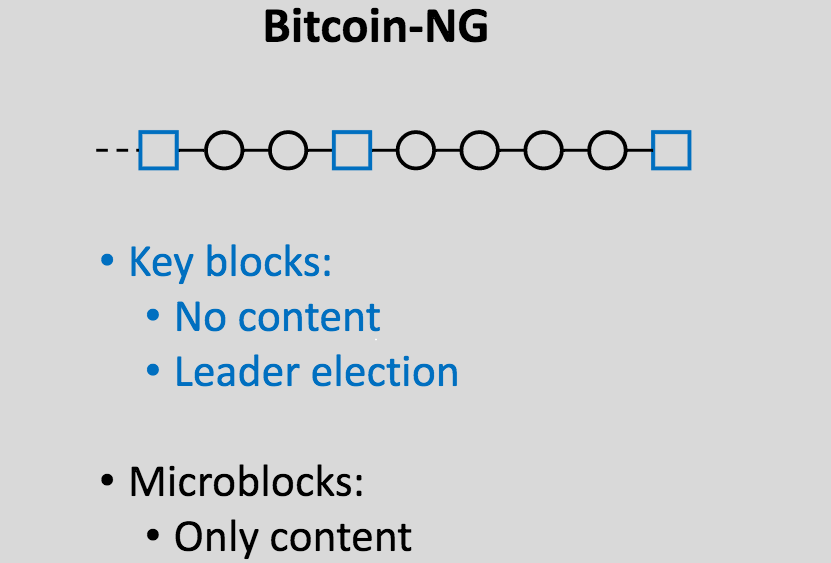

Appendix: Eyal and Sirer’s Bitcoin NG

A recent interesting proposal presented at the Scaling Bitcoin conference in Montreal is the idea of splitting blocks into two types: (i) infrequent (eg. 10 minute heartbeat) “key blocks” which select the “leader” that creates the next blocks that contain transactions, and (ii) frequent (eg. 10 second heartbeat) “microblocks” which contain transactions:

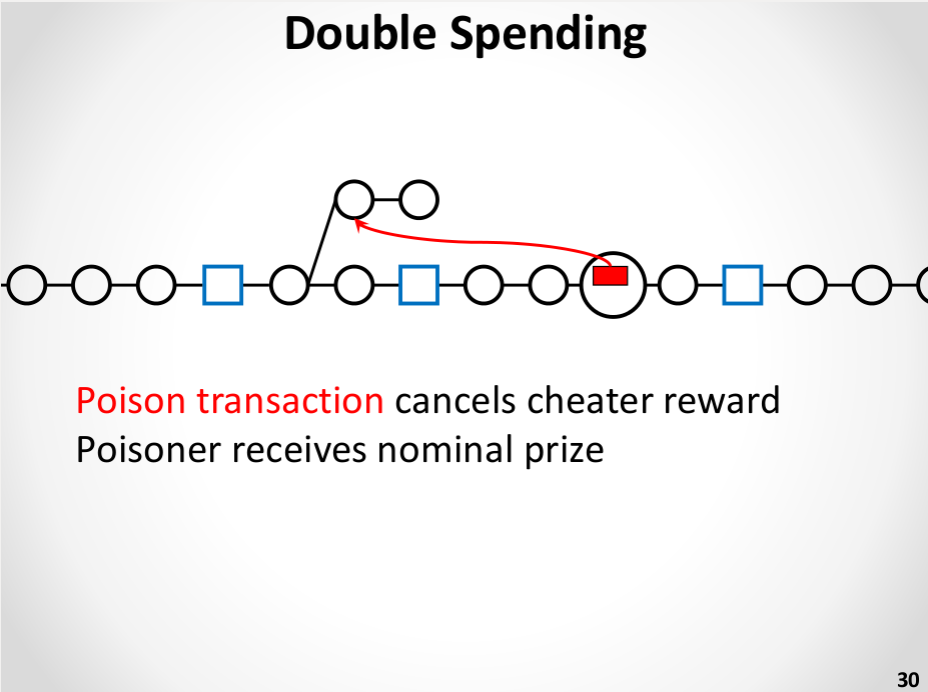

The theory is that we can get very fast blocks without the centralization risks by essentially electing a dictator only once every (on average) ten minutes, for those ten minutes, and allowing the dictator to produce blocks very quickly. A dictator “should” produce blocks once every ten seconds, and in the case that the dictator attempts to double-spend their own blocks and create a longer new set of microblocks, a Slasher-style algorithm is used where the dictator can be punished if they get caught:

This is certainly an improvement over plain old ten-minute blocks. However, it is not nearly as effective as simply having regular blocks come once every ten seconds. The reasoning is simple. Under the economically-bounded attacker model, it actually does offer the same probabilities of assurances as the ten-second model. Under the BFT model, however, it fails: if an attacker has 10% hashpower then the probability that a transaction will be final cannot exceed 90% until at least two key blocks are created. In reality, which can be modeled as a hybrid between the economic and BFT scenarios, we can say that even though 10-second microblocks and 10-second real blocks have the same security margin, in the 10-second microblock case “collusion” is easier as within the 10-minute margin only one party needs to participate in the attack. One possible improvement to the algorithm may be to have microblock creators rotate during each inter-key-block phase, taking from the creators of the last 100 key blocks, but taking this approach to its logical conclusion will likely lead to reinventing full-on Slasher-style proof of stake, albeit with a proof of work issuance model attached.

However, the general approach of segregating leader election and transaction processing does have one major benefit: it reduces centralization risks due to slow block propagation (as key block propagation time does not depend on the size of the content-carrying block), and thus substantially increases the maximum safe transaction throughput (even beyond the margin provided through Ethereum-esque uncle mechanisms), and for this reason further research on such schemes should certainly be done.